Posted September 21, 2022

The Interview – Steven Elliott Jackson

Steven Elliott Jackson

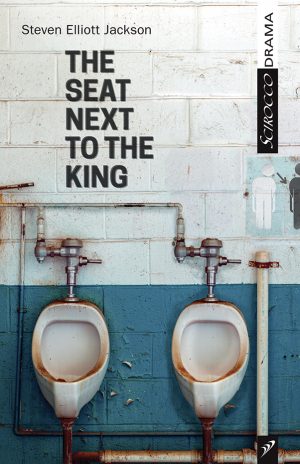

Steven Elliot Jackson is a playwright and the co-artistic director of Minmar Gaslight Productions and its family theatre company, 3 Little Bears Productions. His plays include The Seat Next To The King (which won Best New Play at the Toronto Fringe in 2017,) The Leaves Beneath The Trees, Statue Of Limitations, Three Ordinary Men, (which won Best New Play at the Hamilton Fringe Festival in 2020). Also in 2020, Jackson premiered the historical audio play, Sarah/Frank and the video drama, The Cage at the Toronto Fringe Digital Collective. In 2021, his script The Kindness Of Murder premiered at Next Stage Community Booster, and his play The Laughter premiered at the Hamilton Fringe Festival.

Steven, your play The Seat Next to the King presents us with two characters whose lives intersect with political power, homophobia, and racism. What compelled you to tackle these large and complex themes?

Well, I guess I hope as playwrights we challenge ourselves to tackle these topics. I don’t think I set out to do it, but I let the characters tell me who they are, and these topics are integral to who these men were. Our world is filled with many intersections and that makes any play complicated. It’s less being compelled to write about the topics than the topics needing to be part of these characters.

Three Ordinary Men, recently nominated for five Dora Mavor Moore Awards (including Outstanding New Play,) explores the tragic deaths of civil rights workers Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner. The Seat Next to the King explores what might have happened if Martin Luther King’s trusted friend Bayard Rustin and Lyndon Johnson’s aide Walter Jenkins had had a relationship. Both of these plays are set in the 1960s, both plumb the inequity between white men and black men. What do you see in that era that helps to inform 21st-century discussions about race?

It’s interesting that my love of history is really for eras earlier than the sixties, but as we move forward in time, it’s becoming a decade connected to us that seems long ago and yet is still within many people’s lifetime. Race is a constant topic but looking at the 1960s allows us to see how far we have come and yet still see how far we need to go. I think that we truly see the integration of white and black lives in that decade in a way never before experienced. The start of seeing where equality was wanted by more people and Black voices were being heard—I might add, through mediums that reached larger audiences. We truly don’t realize the contributions things like radio, TV and the internet have made to society, for good and bad.

This year at the Toronto Fringe Festival you had not one, but two plays running: The Garden of Alla, a glimpse into the life of Alla Nazimova, a proud bisexual woman in 1920s Hollywood, and The Prince’s Big Adventurer, a musical for kids aged 5–12. Obviously, these are two very different shows aimed at different audiences—but I’m wondering if you would compare and contrast for us. Do you take a different approach when you’re writing for kids? Are there similarities in these two stories?

Well, both were queer stories, which I go back to now and then. Adventurer was a dream come true, a gay fairy tale where I wrote the book and lyrics. It was always something I wanted to see on stage, something for kids and parents alike. As for Garden, it was another wonderful story for me to tell, queer history and Hollywood, which both always intrigue me. While they offered different writing challenges, mostly in tone, it was nice to play with a little more comedy in my writing. In both cases, it was about queer voices being able to speak for themselves and dealing with the struggles of being honest.

One critic called The Garden of Alla “an urgently relevant queer history.” Do you feel that the same kind of religious repression that befell queer artists like Nazimova a century ago is a threat to today’s LGBTQ2s+ community?

Are there still forms of repression of voices? Of course, but often we find struggles within queer communities to recognize different aspects of the community, let alone the large community of human beings. We have taken the idea of individualism to extreme new angles and I think that’s what makes it even harder to connect in the community—and theatre is one of those places where connection is possible. We strive so hard to be seen as individuals that we often fail to recognize people with struggles that may be similar. I’ve always been a writer who tries to write about opposing people and how they connect, especially when they can’t see it. We live in a world with more ways to connect and we connect even less than we did before because we lack the ability to do that out in the non-virtual world. I can see that in the queer community and I see it in many other ones too.

Several of your plays delve into the subject of race and racism. The Black Lives Matter movement has caused many Canadian theatres to evaluate whose stories are being told, and who is telling them. Why do you think it’s important for white artists to examine racism alongside their Black colleagues?

Because it doesn’t exist without them! In order to have a talk on racism, having the person who is being called on racism not being there seems counterproductive. As writers, we are a part of every play we write whether there is a character in the play named Steven or not. When I write about racism in my plays, I’m actively going outside of my experience and learning someone else’s perspective. I want an audience to see where they are in the discussion, not talk down to them. And I can tell you that I get flak from people of colour and white people alike when I write. And that’s good because maybe it calls out blind spots that I may have. I would rather bring the blind spots out than sit there and only write about me. That’s boring theatre. Writing about someone who isn’t you is a risk and I won’t stop taking those risks.

Do you have a piece of playwriting advice for us?

Write what you know and write what you don’t know all at the same time. It’s called curiosity. It’s what makes us want to figure out how to make this place a better world and see where we fit into that solution. No matter who you write about on the page, especially with history, these are human beings who lived before us and they lived in a particular time. They have so much to tell us.