Posted October 9, 2025

The Interview – Sean Dixon

Sean Dixon

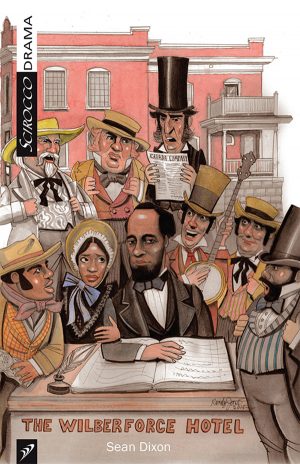

Sean Dixon is a playwright, novelist, and banjoist. His plays include Orphan Song, Jumbo, The Orange Dot, The Wilberforce Hotel, A God in Need of Help, FRANCE — or The Niqab, Right Robert & His Robber Bride, The Gift of the Coat, Lost Heir, The Girls Who Saw Everything, Aerwacol, Billy Nuthin’, The Epic Period, Sam’s Last Dance, The Painting, District of Centuries, and Falling Back Home. Sean lives in Toronto with his wife, the multi-award-winning documentary maker Katerina Cizek, and a daughter whose brilliant, funny, stubborn character permeates his current work.

Sean, you’ve got an impressively large body of work; your plays and novels tackle a wide range of subjects and embrace a number of different styles. Do you think that there are thematic threads that run through your work?

I think I still have a tendency to look for the heightened moment, the pause for a feeling of awe, the risk to your suspension of disbelief where you have to rely on a little faith. I don’t think I can write without the feeling that I’m risking something, from a storytelling point of view. I feel it’s important to surprise myself, which is the only way I can be sure to surprise anyone else.

But that’s style more than theme, I guess. Thematically, I’m drawn to stories about how a person can transform at a deep level through profound encounters with others, or sometimes through a work of art, often in ways they can barely articulate, and I sometimes look for the path that might elevate these encounters onto a mythical plain. Could be an individual or a group of people. (I’m a sucker for stories of found families, like Guardians of the Galaxy, say.)

The Metamorphoses of Ovid is a touchstone for me, with its tumbling procession of psychic and physical transformations, along with the Epic of Gilgamesh, which features the most profound psychological change of a title character in all of literature. I’m not interested in adapting those stories, necessarily (though I did adapt Gilgamesh); I’d rather find new stories to tell that exist in that life-and-death terrain. I search for these kinds of stories, perhaps, because I had an older brother who was a hero to me, who died when I was ten. That story is addressed pretty harshly and directly in my first play, a solo piece called Falling Back Home, that I performed back in the nineties, before meeting any publishers.

Other examples: in The Orange Dot, a woman convinces her fellow city worker to become a willing sacrifice in the war against masculine indifference. In District of Centuries, a small community of outsiders is moved by the story of a kid who believes his curse is to cause the death of anyone who gets close to him. In Aerwacol, a husband who has grieved the death of his child has to wait for his wife to catch up with him in her journey through a gruelling prairie landscape of grief — she started late because of having been bedridden for a dog’s age. In The Wilberforce Hotel, a pair of rough men are humbled in part because of their reverence for the musical instrument in their possession (a gourd banjo). The four strong men in A God in Need of Help have their lives transformed by a miracle that may have merely been the effect of the large and lifelike Dürer painting of the Virgin Mary they’ve been tasked to carry over the Alps. In The Girls Who Saw Everything (which started out as a play but was completed as a novel) a Montréal book club’s collision with the Gilgamesh epic sets them on a journey across the world, landing them on the island of Bahrain in the Persian Gulf in the middle of Bush Jr’s war. (That novel contains my personal favourite walk-on character: a Bahraini waterfront inspector who needs to get to the bottom of why a yacht full of barely grown Montrealers have come into his port.)

Finally, the pain and loneliness of the elephant in Jumbo is life-changing for an entire circus company. And the adoptive human parents in Orphan Song need to transform the rules of communication in order to save the life of the neanderthal child who cannot understand a single thing they say.

Jumbo and Orphan Song both feature innovative use of language. In the case of Jumbo, the central character in the play is an elephant. In Orphan Song, parents and child speak different languages. Can you tell us a little about how language works for those characters?

I try to cultivate a text that will demand a heightened physical engagement from performers. This has always been my goal since the early days of making text for the collective creations of Winnipeg’s Primus theatre.

In my early playwriting efforts, I had a strong belief in tapping into a certain kind of rhythm and to use the energy of storytelling to heighten everyday experiences to the level of myth. I knew I was succeeding because I was inspiring other artists: a xerox of the stage manager’s copy of my early play The End of the World Romance was smuggled out of the Blyth Festival and studied by a teen with writerly aspirations who used it as a springboard to pen his indie bestselling debut novel. Later, a colleague sat at the back of the theatre to watch my solo play Falling Back Home over and over again. He wouldn’t tell me why, but later when I went to the opening night of his play, I heard the effort to emulate my cadences in his storyteller character. These sounded pretty laboured to me, so I was chastened at the end when the audience rose to its feet.

Beyond the rhythm of storytelling, I’ve come to love the energy of passionately inarticulate characters. I think I have at least one aria of incoherence in every play I‘ve ever written, but Orphan Song gave me the chance to create a symphony of the musically inarticulate: in a story about the life-and-death necessity for communication under conditions that make it all but impossible (adoptive human parents of a neanderthal child), I was challenged (by director Richard Rose) to cut all stage directions and fill the script with noise — screams, cries, barks, growls, whistles, notes (and a small collection of elliptical words) along with musical staves (for the neanderthals’ musical language) — whose intentions would have to be uncovered through the process of humming and howling through them. And I gave the human characters a vocabulary limited to just a few dozen words, using a linguistic tool called the Swadesh list. It’s remarkable to me how expressive you can be within that kind of limitation. Some critics mocked me for it (I was a bit shocked by the controversy, frankly), but it did what I wanted it to do and I was content.

Orphan Song is written with a lot of gibberish. When preparing it for publication, I tried to make the text more readable by providing notes and letters, essays and photos and pleasing images of the music (which was provided thanks to the skills of Phoebe Hu, who corrected my poor transcriptions of the Neanderthal’s sung language.)

But I would recommend to readers that, if they want to understand the play itself, they should read it out loud.

As for Jumbo, a favourite memory about that project was being told by the sound designer Deanna Choi that she relished the opportunity to create an emotional sound palette for a character that could not speak. I do feel an essential job of a playwright is to create challenges for the collaborators, and even to find scenic excuses to inspire the collaborators to merge their disciplines, as for example when a costume also works as part of the set.

Do you have a philosophy of theatre?

I’ve never forgotten the garish, wordless, full-face character masks that we were shown in school, which had the miraculous power to escape their destiny by transforming their literally carved expression into its opposite: the mask’s metamorphosis happens through a change in intention and behaviour: so the cynic’s twisted smile of contempt transforms into a wild idealism. The puritanical nun dances and becomes lascivious. The cretin raises his ground-sniffing nose to the sky and becomes a spiritual being. They’re simply miraculous — ‘simply’ being the operative word. I think the best theatre is simply miraculous. It can happen without any magic beyond the performers committed to their bit.

I saw a great piece of theatre just the other day at Theatre Direct’s season launch — in a library basement with fluorescent lights: Guardians of the Gods. Its two characters are kids telling one another about their experience of grownups. Some anecdotes are lighthearted, some are absurd, others are harrowing, heartbreaking, tragic. They change their perspectives at will, becoming new characters with new stories and you’re never sure whether that is the game this child pair is playing, or whether the actors are really giving us a vision of a hundred kids. It feels like the former, like true play between this pair standing in front of their plain metal trunk. Occasionally they reach into a hat and read sentences that have been written by real children in other parts of the world. At the end of the play, the performers shed their child personas and offer the members of the audience the opportunity to write down their own thoughts on their own strips of paper, messages that will travel overseas and be read aloud by other actors in other countries playing the children in this play. It’s transformative for us, for the audience, more powerful than any main-stage show with a million-dollar budget. That’s my philosophy of theatre.

You are not only a prolific playwright; you’re also a novelist and the author of a children’s book. What are the challenges/advantages of writing in more than one genre?

I’ll start with the advantages, since they are easier to express: I was trained as an actor, and the deepest part of my training (with Winnipeg’s Primus theatre) was rooted in the belief that an actor is someone who learns how to do things: it was considered important to know how to play a musical instrument, how to perform a handstand, how to present a larger-than-life character in a street parade, how to build costumes and props and sets. And how to write. If you don’t know how to do it, and you need to know it, then you learn it. I believe that my exploration of several writing disciplines has grown out of that practice. I don’t think I’m alone in this: I suspect my more famous novelist/playwright/actor colleague Ann-Marie MacDonald feels very much the same: discovering story and character through writing is an actor impulse, I think… or, I contend… or, I assert!

So the advantage is the creation of an aptitude for learning new things: in being a lifelong learner who can say “yes” to the impulse of creation.

The disadvantages: well, that’s all on the business end, I guess. Business and branding:

When feeling ungenerous, theatre people think novelists don’t understand action and economy whereas literary people might view playwrights as dilettantes who harbour the mistaken impression that playwriting is easier because it requires fewer words. I suspect I’ve been regarded both ways.

Theatre and literature in Canada are siloed disciplines, with distinct support systems that rarely overlap, even when a writer is doing both. So I do think when you try and step into the one realm from the other, you are risking the loss of one supportive community while not necessarily gaining a new one. And if you go back and forth, you might be seen as a noncommittal artist. I had some critical support when I started writing novels that did not return after more than a decade away. There are literary festivals that I don’t have a hope of being considered for — or, I suppose it’s more fair to say I don’t know how to court their interest.

On the other side of that fence, I was warned by an early theatre collaborator that if I drifted around too much, I would be forgotten, and it’s true that he doesn’t work with me anymore. He meant his warning geographically, but the point is well taken for artistic practice as well.

And I didn’t have the first idea how to promote my children’s picture book, The Family Tree, despite getting a shoutout from a CBC summer reading radio segment. I perceived a vibrant community of such writers in social media but had no idea how to penetrate it. It requires a daily commitment and cultivation. I’m not disciplined like that. I can’t make myself see the world exclusively from the point of view of a children’s book writer. And I suppose it’s no surprise, then, that the publisher of that book has not accepted any new submissions from me. I’m not built for the cutthroat business of children’s book publishing, it seems.

The problem boils down to the fact that a writer becomes known for producing a certain kind of work. They’re “branded” with it. I’ve always chafed against that and so I suppose it’s true I have never built a committed, continuous audience for any of it. I imagine it must be possible to generate a reputation for being able to write in radically different ways, and I suppose if I had any real social media discipline (see above), I would create content that is exclusively about inspiring creativity in all forms of writing. Maybe I’ll start doing that. Currently, I use the socials for distraction and doomscrolling, just like everybody else.

The good news for theatre is: these days at least, it feels like the support system around theatre is stronger and healthier than what exists around the literary communities. Newspapers still have dedicated theatre critics, whereas a book review feels more and more like a novelty reserved for the books that are already destined to be bestsellers.

For the novel that I produced last year, I received a total of three published reviews. Thrillingly, they were the best reviews I’ve ever gotten for anything, but, vexingly, they didn’t lead to any more. Three! And not a single one was in a daily newspaper. It was a bit of a shock to see how far the literary support system has fallen in the last fifteen years in Canada.

But, again, I’m an outsider, and I had stepped away from the industry, so I had nowhere I could turn to for guaranteed support. So I’m looking through that filter, and it may be just that I can still count on the support system that is built around the theatre, so it automatically looks healthier to me. From the point of view of the literary editor of a journal or newspaper, I’m just some amateur whose written a few skits and is now trying to peddle a big pile of prose. Get in line, kid.

Your latest novel, The Abduction of Seven Forgers, was described by Quill and Quire as:“A novel as sheerly entertaining as it is profound.” Tell us more about the book.

It’s about a wealthy Korean art collector, Jackie Lin (named after my daughter’s beloved taekwondo instructor) who has been cursed in his life to purchase forgery after forgery after forgery. He identifies and seeks revenge against the several artists who have wronged him. But he also senses there is a deeper reason for the curse and harbours a quixotic hope that these art forgers will be able to help him somehow. It takes place in a single setting — a big house in Willesden Green that I stayed in when I went to London for the UK launch of The Girls Who Saw Everything fifteen years ago.

Writing the novel was good company for me during the lockdown. My characters were trapped in a house just like I was, bound in a nutshell, and I was keen to see how I could turn them into kings of infinite space, with none but a few bad dreams. I wanted to write about things in this world that I loved. I had started the novel and set it aside several years earlier, when my daughter came along, having just introduced the characters and given the unnamed art collector his spectacular entrance. But I never forgot the characters. Then, in January of 2020, I realized that I didn’t want to begin writing a new play because I knew we were going to start rehearsing Orphan Song in March, and I was very excited about that. So I decided to pick up the Forgers manuscript and see how far I could get before rehearsals began… And then rehearsals didn’t begin.

It was at Tarragon, and I remember Courtney Ch’ng Lancaster telling me the week before I was meant to begin how the audiences for Three Women of Swatow were uncannily quiet, no one daring to make even the littlest cough.

The theatres shuttered and I was left with my novel. I thought it likely at that time that I would never write for the theatre again.

Can you give us a sneak peek of what you’re working on now?

I have three plays that I’m determined to get mounted. I don’t want any to be left behind.

The first is a show that I’m hoping Blyth will do, called Trial By Banjo, which is a celebration of music built around the story of a corporate lawyer who destroys his life by developing a sudden and incurable desire to learn how to play the banjo. In the spirit of Jean Anouilh‘s Ring Round the Moon, the actor playing the central character also plays his primary nemesis. Hello, Gil Garratt: will you play this part for me?

The second is an adaptation of a Victorian novel from the 1860s about a young boy who is befriended by the North Wind, but who really is suffering from an illness (diphtheria, say) and who dies at the end. When I read the novel, a couple of years ago, I had the overwhelming feeling that the author was trying to write something that would bring comfort to people who were surrounded by the tragedy of dying children, an inescapable reality of the time. He was presenting death as a sort of grand adventure in the company of a spirited old auntie who also happened to be a bringer of shipwrecks.

For reasons that would be long-winded to get into here, I felt an irresistible compulsion to move the setting of my adaptation forward just over half a century into the era of vaccines, with only a few adjustments to some of the characters (including a beloved horse), and to rescue the boy from his formerly certain fate. It’s called A Boy, A Horse, and the North Wind, adapted from George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind. I feel so strongly about it that I tell people my adaptation was the prophetic story MacDonald was trying to write: he had all the elements to rescue his central character from certain death, but his tragedy was that he couldn’t see the future quite clearly enough.

I haven’t found a collaborator for this play even though it’s really the most urgently topical thing I’ve ever written.

Finally, I’ve got a play, being developed at the Tarragon, called Achilles At the End of the World. It concerns an aging American soldier walking into a bar the night before his deployment over the northern border, to sit down and wait for a date who never shows. He immediately stops caring, though, because there’s an inexplicable spark with the aging bartender. But he has a sidekick — part wingman, part fluffer, part praise-singer, part nostalgic jukebox musician — who cares a LOT, and who is trying to keep the soldier’s eye on the ball and well prepped for his “night of pie” as well as the morning’s deployment.

And the bartender has a sidekick too, a spirit who will eventually take over and rejuvenate her tired body, who wants to kill any man who walks into this bar, including this one.

These two sidekicks keep each other in play while the pair try to get to know each other over top of and underneath all the noise.

So the play is essentially a four-handed two-hander: a surreal meet-cute for aging Gen-Xers, it recently occurred to me that it is perhaps a sort of wizened, aging sequel to Fight Club.

Oh, and I have a new novel coming out in the spring of 2027 (I think?) called PROTECTOR, which is my final, most personal statement (after Orphan Song and The Family Tree,) on the theme of adoption and attachment. It’s about the patsy in a ransom scheme, tasked with looking after a kidnapped baby, who develops a bond with a toddler that, up to that point, was believed to have attachment disorder.

Finally, if you could give one piece of advice to an aspiring writer, what would it be?

I’m in no position to give advice. I’ll give something and then state its opposite. Stick with one artistic discipline! Unless you don’t want to! Explore your desire to go down a certain path even if the prevailing wisdom tells you not to! Or don’t! Use your talent instead to find out what people want and then give it to them! Believe in yourself! Don’t underestimate the power of a community! Whether it’s comprised of collaborators or friendly rivals is up to you!

A witch once told me that a writer is like a bear in a cave, but you have to also come out of the cave if you’re going to find things to write about. I can state that bit of advice with confidence because it didn’t come from me.

My favourite writing advice for a playwright is Molière’s line from The Misanthrope: “Time has nothing to do with the matter.” You can accomplish great things as a writer over the course of an afternoon. So don’t hurry, but don’t wait either.

-

Orphan Song

$15.95 -

Jumbo

Price range: $9.99 through $15.95 -

The Wilberforce Hotel

Price range: $9.99 through $15.95