Posted December 15, 2025

The Interview – Natalie Meisner

Natalie Meisner

Natalie Meisner is a professor, a playwright, a poet, a mom, and now a podcast host (not necessarily in that order). She was born on the Mi’kma’ki/South Shore of Nova Scotia where she began her curious life by reading, with wild abandon, all the books that came through in the town bookmobile. She has seven full-length books in various genres to her name, was Calgary/Mohkinstsis’s fifth Poet Laureate, and teaches creative writing at Mount Royal University where she loves helping other writers find their voice.

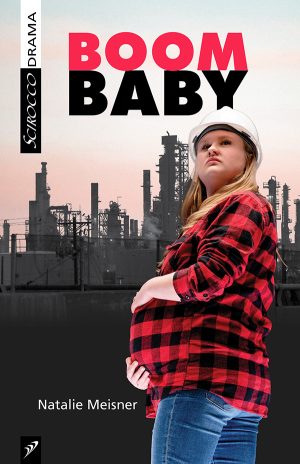

Natalie, we recently published your play Boom Baby, about a young woman working in the oilfields who becomes unexpectedly pregnant. Can you tell us more about the play?

Thank you! I am thrilled to have this play, a Canadian National Playwriting Competition and Alberta Playwriting Competition winner, published by Scirocco. Boom Baby tells the story of Iona, one young hard-working woman who is in the middle of trying to provide for herself and to survive and thrive in a work environment that is challenging for women. She is far from home and without many supports. When she becomes pregnant after sex with a friend that was more about comfort and human contact than romance, her fate hangs in the balance. Iona contemplates all her options, such as making the arduous trip back to the city to end the pregnancy, adopting the baby to a couple who work in management for the company that employs her, or finding a way to raise the child herself. When the couple offers to pay her for surrogate services, she ends up asking herself—and the play also wants to ask—if there is any limit in terms of what can be bought and sold when it comes to the next generation. In a work camp environment, everything has a dollar value, and I wanted to push this logic to the limit to see what, if any, solutions human creativity could provide. Everyone needs to make a living and no one should be shamed for working to provide for their family, but what is the price of that work and who benefits? In Boom Baby we see the big, generational story made personal in the lives of Iona, her compatriots and her unborn child. We also meet the Albertans who are higher up the chain and benefit more fulsomely from the industry. What I wanted to do in this piece was to take this big issue of extraction and who benefits/who pays the costs and make it personal by telling it through the lives of working people, like the ones who raised me and whom I grew up with.

How did the idea present itself to you? Did you begin with Iona’s story? Or did the themes give rise to the plot and characters?

I grew up in a fishing family in SW Nova Scotia/the Mi’kma’ki, where in the space of two generations, small-scale sustainable single boat fishers have been displaced by huge ocean draggers that tear the sea bottom and send profits overseas. In each generation we have lost family to the sea as they venture further offshore in worse conditions to make ends meet. Many also traveled to the west coast or to the north to work in mining. When I, too, found myself in Alberta for work, I began to take note of some of the similarities between fishing and mining, particularly in the lives and families of the people working in those tough industries. Both relate to the “tragedy of the commons” idea outlined by William Foster Lloyd and then reintroduced by Garret Hardin, that looks at how individuals or companies, when given access to a shared resource will tend to overuse it, eventually destroying it for everyone. Then it struck me how many of the issues I had seen playing out in the fishery were also happening in oil extraction. The environmental devastation, how extractive practices are practiced upon the earth but also upon the human beings struggling to survive and thrive upon her.

The first inspiration for this play came as two images: the green /blue tributaries of the Athabasca River that provide the watershed for the continent… and an unborn child floating peacefully in the watery world of the womb. The images flickered in my mind’s eye, then became one. Then the characters (inspired by family, friends and loved ones) began to speak, each of them with their own valid and differing point of view and I knew I had to follow this play wherever it took me. When I wrote the first notes for this piece, I didn’t have children of my own and now I do, which brings the question of what we leave to the future even closer to home.

Your non-fiction memoir, Double Pregnant: Two Lesbians Make a Family, is the account of how you and your partner, Viviën, become pregnant and give birth to your sons within a few weeks of one another. The book ends with the birth of your second son. How do you think that parenthood has changed your writing practice?

Double Pregnant felt like a bridge between my other writing self, (pre-mom) and my current writing self. As a young person, I had an awareness of how it seemed that so few women had been able to navigate both being an artist and motherhood. Also, as a queer person, family life seemed a bit out of reach for me. We could not even get married at that time. I joke around with some of my theatre colleagues and my students about how becoming a mom has made me be a more human human against my will! Not to say I was insensitive as a younger artist, it is just that I felt very driven (or perhaps it is better to say “called”) to write and create, which came right out of some of the raw stories I saw around me. My mom had me very early (17!) and did an amazing job of raising me, but we did not have generational support, connections to arts/education, nor access to such things. If I wanted to be an artist, I knew that making a living was no joke. I would have to take other jobs to support myself, and also live lean and make sacrifices. At one point in time, I gave up my apartment and used my rent toward keeping the repurposed store that our theatre company was using as a space. I took my showers in a big industrial sink, but no matter, we were making shows! I think I might have been fairly uncompromising, if not with others then certainly with myself. This really changes when you have other tiny humans that depend on you, suddenly—yes, the artist in you is still alive, but it takes a back seat to the sacred duty of caring for a child, in our case two children. I have a total reverence for motherhood/ parenthood. To do it well takes EVERYTHING you’ve got. So does being an artist… but when they can co-exist, it really can make your art more empathetic/open and human. It also makes you a better manager of time and gets you over any angst over writer’s block, etc. You no longer have any time to waste.

You’ve also written a beautiful book for children about a family with two mothers, My Mommy, My Mama, My Brother & Me (illustrated by Mathilde Cinq-Mars). How do you think we’re doing with regard to representing LGBTQ+ families in Canadian literature and entertainment? Also: Do you worry about censorship, given the current political climate in some provinces?

At the time when I wrote this book there were really only a few books that showed LGBTIQ+ families at all, and none that showed a family like ours that was both two mom and bi-racial. Reading book after book to our kids where even the bears and owls seemed to follow rigid nuclear family roles did make me want to try my hand at writing a book for children. Specifically, I wanted to make a beautiful book that both parents and kids would want to come back to together, so that kids could learn to read and adults would find some layered meaning in the text and, as you noted, enjoy the artwork. Cinq-Mars is one of my favorite illustrators, so it was really a dream to work with her. Finally, I wanted to include the ways a family can be diverse in the book, but without making it the “problem” of the book. Instead, the book is more of a “provocation of wonder” book where you take a walk over the beach with the family and learn things, not about whales and dolphins (lovely creatures, but already so popular,) but about some of the lesser-known creatures like gulls, skates and sea urchins. There is also a message in there about building community and opening our doors to our neighbours. The book seems to have caught on, as it has just gone into its second printing.

Do I worry about censorship? Yes, absolutely, considering all that is going in Canada and around the world. Yet, whenever I feel down about this, I go and talk to a historian. They remind us that censorship has always deployed by the “ruling class” and those with power, no matter how they came by it. One of the jobs of the writer and artist to use our skills to resist it.

In addition to your work as a playwright, you’re well known as a poet, and, in fact, you were Calgary/ Mohkinstsis’s fifth Poet Laureate! What do playwriting and poetry have in common? How do the approaches to writing in the two genres differ?

Something I always think about is the way that, historically, the two formats were fused. Classical Greek plays, Shakespeare and his contemporaries, all plays up until the 17th century were written in verse. We tend to forget this, since the prose play took over and (although there are lots of very alive experiments and offshoots that still include poetry,) plays seemed to become more and more kitchen sink-y or realistic. But for me the two forms have something in their guts and heart that are still fused and it is why I keep coming back to them. They are the forms that are, perhaps, the most demanding to write. You may not have one extra bit of fluff. The perfect words in the perfect order. A play like a kind of exquisite blueprint that invites first a team of co-creators, then the audience in. Both make art out of the everyday words that come out of people’s mouths. I use these forms to try and wrestle with things I do not understand. Frequently I will write a poem about something, stew on it for years… and in going back to it, discover that it is spawning a play!

What are you working on these days, Natalie? Can you give us a sneak peek of any upcoming projects?

Yes, I am at work about a trilogy of plays that are set in Nova Scotia where I grew up. The first one, called AREA 33 debuted last summer and will tour in the spring. The second one, called SubHuman will tour to Dublin, Ireland in the spring and have its Canadian premiere this July. The third one, with the working title (that scares me a bit, yet I feel it is right) of M*therf*cker is about what happens to a fishing family when their father and brother are lost at sea along with the boat that was their livelihood. It is the first time that I have written plays that are linked, to one another, sharing characters and setting. It feels like one of my most demanding projects to date. I also have a new kid’s book and a new book of poetry in the works.

-

Boom Baby

$18.95