Posted November 17, 2025

The Interview – Michele Riml & Michael St. John Smith

Michele Riml

Michele Riml is a critically acclaimed playwright from Vancouver, British Columbia. Michele’s first play Souvenirs won the BC Young Playwrights Search. Some of her plays include Under the Influence, Poster Boys, RAGE (winner 2005 Sydney Risk Award), On the Edge, and The Amaryllis, which was produced by The Search Party and premiered at the Fire Hall Theatre in Vancouver in the fall of 2020. The Cull, co-written with Michael St. John Smith, premiered at the Arts Club Theatre in 2023. Michele’s play Sexy Laundry has been translated into more than fifteen languages, with ongoing productions in Canada, the United States and Europe, along with its sequel Henry and Alice: Into the Wild. Michele’s plays for young audiences include The Skinny Lie, The Invisible Girl and Tree Boy, published by National Geographic and most recently produced in Athens, Greece. Her most recent play, She Shoots, She Scores!, an adaptation of hockey legend Cammi Granato’s book I Can Play, Too!, will premiere in 2026 with Green Thumb Theatre. Michele is an FPA graduate from Simon Fraser University. In 2008, she was nominated for the Siminovitch prize.

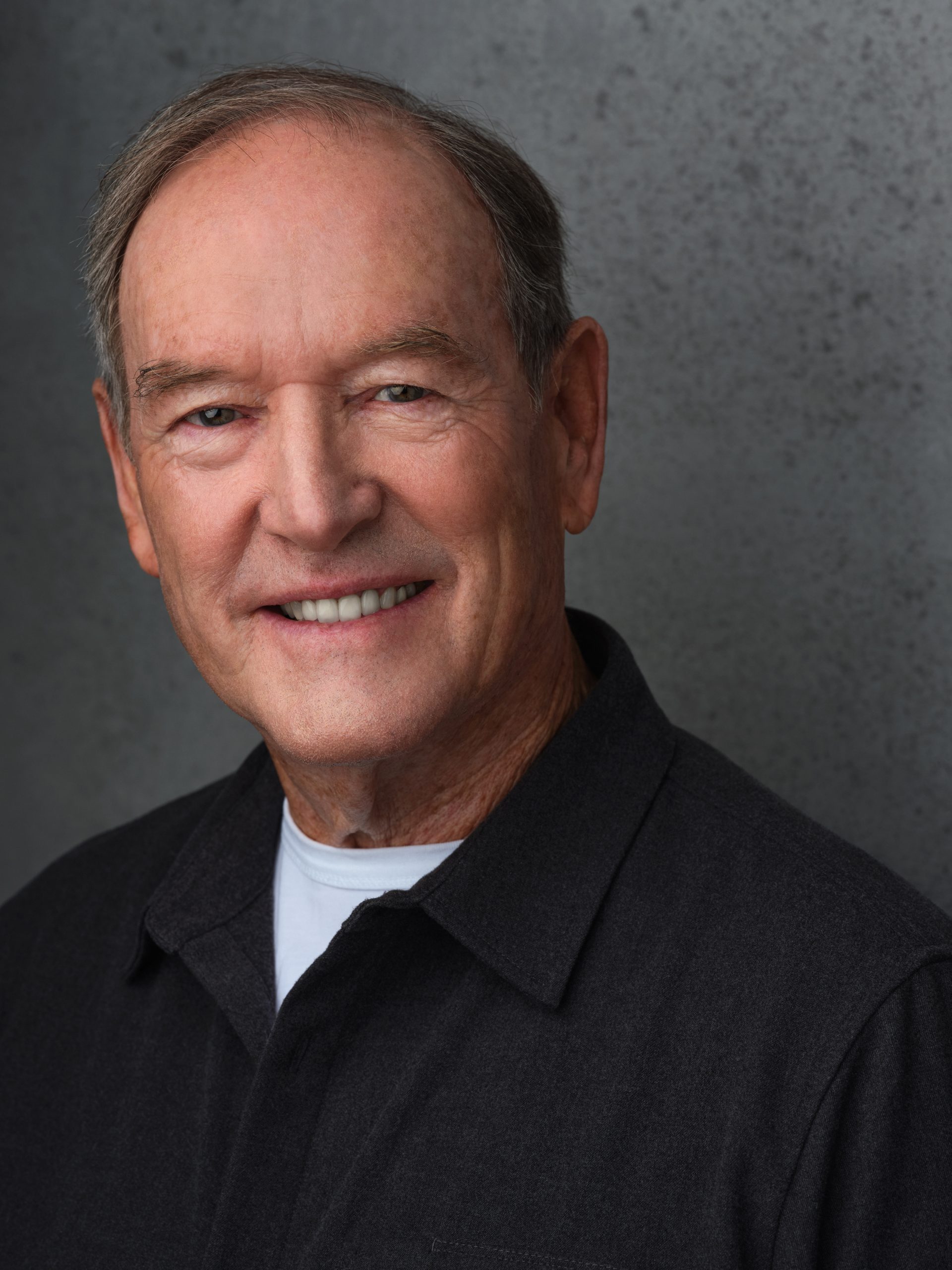

Michael St. John Smith

Michael St. John Smith is a writer, film actor, and screenwriting instructor. Michael has authored four stage plays, including the Jessie-nominated Slaying Dragons, The Biz and The Bridge (co-written with Michele Riml for Pi Theatre and produced as a CBC podcast.) His fourth play, The Cull (co-written with Michele Riml), premiered at the Arts Club in January, 2023. Michael has also written several commissioned screenplays. These include an adaptation of the Ivan Coyote novel, Bow Grip, with Telefilm Canada, The Pen and the Sword, an animated TV pilot for Devine Entertainment, and most recently, Archangel, an original sci-fi feature co-written with New York Times best-selling author, William Gibson, with support from the Harold Greenberg Fund. Archangel was adapted as a graphic novel and is currently being developed as a TV series with Copperheart Entertainment. Michael graduated from Harvard University with honours in English Literature.

I’d like to start by asking you a little bit about the process of writing The Cull. Is this the first time that you have worked together on a play or a screenplay?

Michele: We worked on a small piece called The Bridge for Pi Theatre Company, a twenty-minute play that was part of a series of plays. So we did work together on that.

Michael: We were aware of the risks!

How did you come up with the idea for The Cull?

Michael: We had a friend who invited us over for dinner, and at the time we weren’t thinking of working on anything together. But there was a government employee at the dinner who had been working on the wolf cull, and he started talking about it. I think there were about six or seven people at the dinner discussing it. Afterwards, we both got into the car and we said, “Boy, you know, that would be a great idea for a play!” The metaphor of the way wolves conduct themselves and the way people conduct themselves. Morals and the idea of morality, the idea of the good of the pack and that sort of thing. So we were kind of fascinated with that idea.

Michele: And I think there was an obvious connection, which was this friend of ours often hosts what he calls a “meat party” or “carnivore party.” And it was one of those, so he had all this meat there. And then we were talking about wolves! So the connection between the meat and the wolves, that became a big image in the play, this red meat. It connected metaphorically and visually right away.

Also, I think one of the reasons we chose to write this together was that it’s a play about marriage. It’s a play about long-term relationships, friendships, marriages, and men and women. So it felt really right for both of us to have input into that. It was really fun to work through the various characters. We did a lot of character work, a lot of backstory, figuring them out, going back and forth with our own points of view about why people do what they do. That was the fun part of the process for sure.

Michael: It was important that the characters were friends, but that there was also someone who had not grown up with them, so that there were these differing, subterranean motives going on, which emerged slowly. That gave it a sense of tension and a dynamic within the context of what we were trying to do. It was fun to work on.

Can you tell us a little more about the mechanics of how you worked together? Did you set parameters for when you would work on the play, or did it take over your lives at times?

Michele: Our son was living at home at the time and he was about seventeen. So we still had our life and everything. But I think that one of the good things about it was that we could be standing in the kitchen having a coffee in the morning and have an idea about something and start talking. An hour or so could go by as we were working out a scene. So we did set certain times to sit down together and to talk about the play first; we worked on the characters and the backstory, but then we began to talk more specifically about scenes. Our son even came out from his bedroom a couple of times going, “Are you guys fighting?” And we weren’t fighting. We were trying to take on the voices of the characters and enact what they were enacting.

We have separate offices: Mike has a shed out back and I have my own office. So when it came to the actual writing, we each took on particular scenes. I wrote the first thirty pages of the play, and then Mike picked it up and reviewed it, and he wrote the next twenty pages, or whatever. Then we started picking scenes that we wanted to try. We would switch them over to each other.

Michael: In this process, which could be quite antagonistic in some ways, with egos and all that, one of the things that really helped both of us is something that Michele’s very good at. What really trumped everything else was the good of the play, and we both really held that. People always laugh and ask, “How’d you stay married?” But frankly, it wasn’t that big a deal, because of that overriding principle. I think we both saw that. Plus, I think we had a lot of fun while we were doing it, because it was a really good idea. It had a lot of mileage in it, you know what I mean? It was good.

Michele: Also, I’ve written a lot of plays, and I didn’t feel that this was a play I wanted to or could write by myself. So we each had respect for what the other brings to the table, and those things are slightly different. For example, I write with a lot of humour, and Mike has more interest in the deeper philosophical themes. It really helped that we have different things that we bring to the table, but we also have a shared aesthetic—we like the same stuff. That said, we had arguments, and we have a slightly different process when we actually write a scene and then present it to the other one. Mike’s process is: he just puts it down. And then from there, he’s going to work on it. I tend to work it out a bit more before I show it to anyone. So there were a couple of times where Mike would see my scene and he’d go, “Yeah, great. No, I really think we’re going somewhere with this. We can work on this.” And I’d read his scene and go, “What are you thinking? This isn’t it at all.” To his credit, he didn’t take it personally. But we did have a couple little fights while still understanding that we were both just coming at it, trying to work something out. And we always did. Like Mike said, if you put the good of the play first, then it’s just better. Which is interesting, because that’s the theme of the play, putting the good of the pack above your own ego and agenda. Even when we disagreed and walked away from each other, each of us came back at different times to go, “Yeah, you’re right.”

The only time I got legitimately frustrated with Mike was when he’d start editing the wrong draft!

It feels like the overriding theme of the play played out in the process.

Michele: I mean, we’ve been married for twenty-eight years. And we were talking about marriage and infidelity and long-term relationships, and what makes a relationship work. So there were lots of good things to discuss. We felt like we’d had some experience, obviously, being married for so long. So that was helpful, too.

It sounds almost as if you acted like dramaturges for one another, in a way.

Michele: Stephen Drover, the actual dramaturge (and author of the foreword for the book,) made a comment when we gave him the first draft, which was, “I have never read a first draft that’s so tight and already there.” I wish we were geniuses, but we’re not. That “first draft” was actually a draft we’d gone over together about four times. One thing I really respect about Mike is he’s super particular; once the stuff is down on the page and we’ve agreed to it, then he fine-tooth combs it for edits, making sure everything makes sense. He goes over and over it. So when we handed in that first draft, we’d already done some work on it, which is not a bad way to go.

Michael: But having said that, it changed a lot.

Michele: We didn’t even know what the second act was after we finished the first draft. We wrote the first act and handed it in, and we were like, what happens now?

I was acting out stuff in the living room. I was down on my hands and knees and going, “Okay, you’re standing on my hand. And how does that work?” And Emily crying about the eggs, I was doing the monologue because I had a dream that night before about it. No wonder our son was going, “What are you guys doing?!”

My final question: Is there another collaboration for you in the near future?

Michele: Right now I’m working on a new commission for the Arts Club called Salt, which is a play with music. Through the years, I’ve always used Mike as my first reader and the person that I’ve batted ideas back and forth with. I think he uses me in the same regard. So even when we’re not specifically working on something together, we do get together and talk about our work. We’re each a good resource for the other. But I would work together again. Would you?

Michael: Yeah, I would, I would, too. I mean we are both very independent in the way that we have our own ideas. We work on our own things. I’m also an actor, so I spend a lot of time doing that.

Michele: The idea was right.

Michael: Yeah, I would definitely do it. It’s funny, we also just worked on a film version of Michele’s play Sexy Laundry. We work well together. We respect each other and that’s really important.

Michele: There are pros and cons to collaborating—in general, not specifically in regard to working with Mike. Part of what I like about being a playwright is to be alone, coming up with things and kind of pottering around. Letting stuff come up and writing things and not checking in with anybody about it until I feel comfortable with it. But the great thing about working with someone is it really speeds the process along. “What do you think of this? What do you think of that? What about this?” You’ve got that other person to bounce ideas off or even to take on the roles and improvise it.

Michael: And it varies. Different people do it different ways. I worked on a project with Bill Gibson and he and I would email each other. You know, we’re friends, so we could physically meet. But we never met and talked about it. We literally emailed. I would do a version of a particular thing, and then he would do a version of it. And that’s how that went. It was a completely different process. It just depends on what the project is, I guess.

It sounds like collaborating in person was perfect for this project, where you could create the characters together and say the dialogue back and forth.

Michele: Well, you know, it was really.

Michael: Michele would write a scene involving the two women or something, that would reveal something new about the characters. Then we could go deeper into that, and it changed the way we were looking at certain things. Because those characters became real, not representations of something. We really knew who they were. And then they actually started to dictate and change things. It was good.

Michele: When we were talking, we did a lot of backstory. We did a lot of character work, sitting in our chairs talking in the living room. Then I had to write the first few scenes, because that is definitely my process, finding out what they have to say, what’s actually going on here. But then it was like we were in. It was like, “Okay, good, we’ve got an opening. We know what these people are worried about.” After that we could go back and layer stuff more as we figured out the plot. We didn’t plot the whole play; we discovered the plot as we went along. We really didn’t know the ending.

Michael: Originally, in the first draft we wrote, the whole thing was about revealing this affair that had happened, which never felt like enough. It just felt too pat. The play was demanding a higher level of commitment in terms of what really happens in these situations.

Michele: It’s more subtle, that’s the thing. All those things become more subtle.

-

The Cull

$18.95