Posted February 20, 2024

The Interview – Kanika Ambrose

Kanika Ambrose

Kanika Ambrose is a playwright, librettist, and screenwriter. Her play our place was first produced by Cahoots Theatre and Theatre Passe Muraille in November 2022. Her children’s opera Anansi and the Great Light (with composer Nick diBerardino) premiered at Curtis Institute of Music (Philadelphia) in 2019. Her opera Of the Sea (with composer Ian Cusson) premiered at the Bluma Appel Theatre in March 2023, commissioned by Tapestry Opera and Obsidian Theatre Company. Other short works have premiered across North America including celebrated digital work Tak-Tak-Shoo with composer Rene Orth. As a screenwriter, Kanika has worked in several development rooms and is in residence in Canadian Film Centre’s Bell Media Primetime TV Program (2022-2023). Kanika is a graduate of Toronto Metropolitan University and is Associate Artistic Director of Necessary Angel Theatre Company. She was featured as one of Cahoots Theatre Company’s “30 for 30” theatre-makers for their 30th anniversary season. A long-time Scarborough native, Kanika currently lives in Orono, Ontario with her husband and son.

Kanika, your powerful play our place, which won the 2023 Dora Mavor Moore for Outstanding New Play, is the story of two undocumented workers struggling to find a way to stay in Canada. The play centres on two Caribbean women whose lives are made incredibly difficult by the barriers Canada has erected for immigrants from certain parts of the world. Why did you want to write this play? What do you want audiences to understand about women like Andrea and Niesha?

I wrote the play for many reasons; there were a few things on my mind. One was, at the time, my husband and I were filing documents to try and sponsor his mother. So I was becoming intimately steeped in the immigration process and it brought my attention to the barriers that were there. Some of the questions that they ask to fast-track somebody, or the criteria they use in order to consider somebody more “desirable”… There are certain people in the world that would in no way fit those criteria. For example, the country where my family comes from didn’t have a university for a long time. How would you get a university degree unless you had money to leave the country? So there are those kinds of barriers that I recognized in the process. And then at the same time, somebody we were very close to was working at a restaurant (close to where I used to live) and told us about a co-worker there who was getting married to somebody for papers. This was something that I had been aware of since I was really young, like, it’s not news. But I thought about that person who was marrying somebody who she’d just met, and the type of danger that she could be in, marrying somebody that she’s only known a few weeks, being put in that precarious situation. I thought what could happen in such a power imbalance. So those were kind of the two central inspirations for it.

You have worked as an actor as well as a playwright and librettist. You’ve been Associate AD of Necessary Angel Theatre Company, Artistic Producer at the Paprika Festival, and you’re also the founder of a Dominican bélé dance group, Mabouya Dance Company. Does your work in these other disciplines inform your playwriting? If so, how?

I started out writing and performing my own work, so a lot of the characters, a lot of the stories I created through the body, through my acting training. I would do physical exercises to explore character, which then went into the writing. I don’t do that so much anymore, but I still do very much start with character, and I do feel myself inhabiting the characters when I write, so I guess that’s part of the acting training.

I worked in administration at a large theatre company for a long time, and then, as you mentioned, I’m still the Associate Artistic Director at Necessary Angel Theatre Company. I think those pieces are important because they help me to recognize the structures in which our art is carried and held, and it also gives me more respect for the people who produce the work. You know, I really have an intimate understanding of what it takes and what goes into it, and so I feel like I have an appreciation for it. Sometimes when I’m speaking to some of my friends who don’t have that background, they’re like, “Well, why did they do that? Why did they choose that image? Why did they put that out at that time?” And I’m like, “Well, I can really break it down.” I understand the reasons why it had to happen that way, and it doesn’t stress me out. And I let people do their jobs. It serves me well—I just stay in my lane.

And then as a dancer, I think, the appreciation for the body. For one thing, I’ve just had a baby. Every time my body shifts, I’m trying to reconnect to it. Dance really helped me connect to my body and then to connect to my creativity. And so even though I don’t dance anymore, I need that connection. I just had a long walk with my kids trying to connect my body and my spirit. So I think that’s where all those pieces work together to create me as a playwright.

You’ve written several libretti for operas, including Of the Sea, which had a successful run at Obsidian Theatre last year. Where does your love of opera come from?

When I was a teenager, Grade Ten, I went to an all-girls school in the Beaches in Toronto, and our vocal music teacher took us to see Rigoletto at the Canadian Opera Company, and I loved it. Everybody else was kind of rowdy, but I loved it. I was like, “This is high drama!” I could see myself in it. I loved it so much. And I don’t remember how it happened, but I ended up doing a youth program at COC, where we saw Norma, and then we had to adapt a scene in Norma to fit our everyday teenage life. But I loved it. And then somebody sponsored me, like, a patron—gave me free tickets, seasons passes to the opera. Until I was, I think I was 21, because I was in theatre school and was still going. So I saw a whole bunch of opera! And then I forgot about it because I hadn’t seen much opera in English, if any. The COC at the time weren’t doing much of that, so I didn’t know there was newer contemporary opera—until Tapestry Opera had their LIB LAB (Composer-Librettist Laboratory). I was asked to consider applying to it, which I did, and I got in. And then it became very clear quickly that my voice was really well-suited to writing opera libretti. And I enjoyed it, and it felt like a good fit for the types of stories I wanted to tell. So that’s where that all started.

Kanika, your new play, Truth, just opened to great reviews at Young People Theatre, one of which called Truth “TYA done right.” Can you tell us a bit about the play and the production?

Truth is adapted from the Caroline Pignat book The Gospel Truth. It’s a Governor General’s Award-winning YA novel. The book was given to me by a friend when I wasn’t working fully as a writer yet. I was still working at a mid job and she gave me this novel and said she thought that I’d be the right person to adapt it. And when I read it, I fell in love with the characters. We all know stories about what happened to Black people when they were enslaved, but this story, the thing that hooked me in was how it centered the voices of the Black enslaved characters. The book had a young female protagonist who becomes her own agent for change in a really beautiful way. And I thought that that was something that’s rare in these types of narratives. I thought that I could really find my own voice in this piece, and really enjoy exploring it, which I did. It centres on a young enslaved woman—she’s 16 years old, in a Virginia plantation—and her own journey to freedom.

Did you work with Caroline Pignat on the script?

No, I didn’t. I sent her an early draft and a late draft. On the first draft I sent her, she had questions, which I answered, and then I kind of just did my own thing. I sent her the final draft and was like, “Here it is!” And she was fine with it. I think she was very keen on having it adapted, and so that made the process all the more fluid.

-

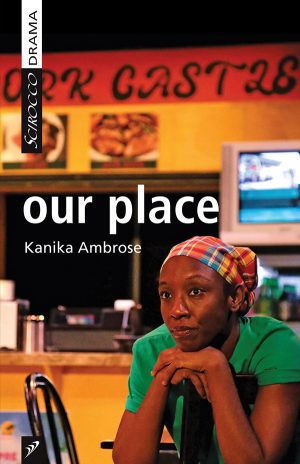

our place$17.95

our place$17.95