Posted October 5, 2021

The Interview – Eric Woolfe

Eric Woolfe

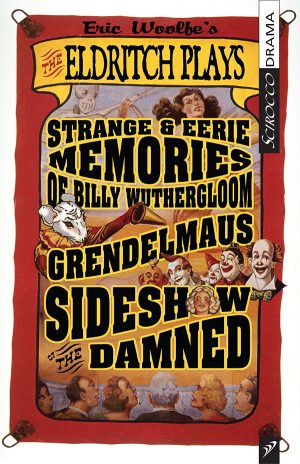

Eric Woolfe is an actor, playwright, puppeteer and magician, and the Artistic Director of Eldritch Theatre, a Toronto theatre company specializing in horror plays using puppetry, live actors, and parlour magic. Woolfe’s work for Eldritch Theatre includes The Haunted Medicine Show, Madhouse Variations, The Babysitter, The Strange & Eerie Memoirs of Billy Wuthergloom, Dear Boss, Grendelmaus, and Sideshow of the Damned. He has been nominated for more than a dozen Dora Mavor Moore Awards, both as an actor and playwright. He is also a three-time nominee for the prestigious KM Hunter Memorial Award. Eric lives in Toronto.

What do you like most about being a playwright?

Honestly, the very best part of being a playwright is being able to lock myself in a basement office for days on end, without having to face other people, and say that I am working and not merely giving in to my anti-social tendencies.

Aside from that, I am very fond of storytelling, and of conquering the challenges of staging scenes in ways that may have never been seen before. I believe that the subject matter we are used to seeing explored in the theatre is remarkably limited. How many plays have we seen about failed love affairs, or broken families gathering in a kitchen for a special event, or political essays disguised as drama? I’m much more excited by, say, alien invasions, or undead monsters, or how average people deal with demented elder gods rising from their slumber to consume humanity. I’m not saying there isn’t a place for, I dunno, a two-act domestic drama about estranged siblings at their father’s funeral. I just think the evening would be more entertaining if the father gets up out of his coffin and tries to eat them.

Who or what do you count among your inspirations and influences?

If I am confined to playwrights for my answer, I will say Charles Ludlam, Charles Busch, Henrik Ibsen, and Arthur Miller. But the list really needs to include EC Comics, George Romero, HP Lovecraft, Stuart Gordon, Universal Horror Films, The Grand Guignol Theatre of Paris, carnivals and sideshows, Buster Keaton, Sam Raimi, travelling medicine shows, fake spiritualists, sidewalk pitchmen, and Raymond Chandler. There are also some magicians who attempted to rethink magic as a narrative art form who have been very influential to my work, like Christian Chelman, Ricky Jay, and Eugene Burger.

What’s the best piece of playwriting advice that you’ve ever received?

David S. Craig once said to me, “Sure you can start writing a play and see where the characters take you, but if you want to actually finish a play and make money, don’t write a word of dialogue till you’ve done a really thorough outline.”

I am a big proponent of carefully structuring a play. You can say anything you want about any subject you want, as long as you have a solid five-act structure that follows the same graph of rising and falling action that your Grade 10 English teacher showed you when you were studying Shakespeare.

I’ll probably get flack for that from some people. They’ll say I’m being rigid and old-fashioned, but I write about cannibalistic mutant babies, and hungry ghosts, and demons that play three-card monte. So, having a traditional five-act frame to work within is important to keep things grounded.

Aside from all that, probably the best advice I ever heard for playwrights was “The greatest words in the English language are ‘The play will be 90 minutes. There is no intermission.’”

Many of your plays have a quality of the… well, the eldritch. You tend to gravitate toward topics that are spooky or weird. But at the same time, your work is often very, very funny. What is it about the juxtaposition of those two things – horror and humour – that you like?

Well-built jokes and well-built scares require very similar mechanisms to be successful. They are both about establishing an anticipation in your audience that something is going to happen. You build suspense towards that something. And then that suspense must pay off in a way that is both surprising and, in retrospect, inevitable. Jokes and scares are machines that run off the same engine.

I also believe that horror should be fun. People want to be scared in theatres, movies, or books, because it allows them to face their fears in a safe environment. They get to mock death. They experience their own mortality in a way that is ultimately life-affirming. Horror plays should be like roller coaster rides for people who get motion sick. Laughter uses many of the same psychological muscles as fear. We laugh for many of the same reasons we scream. So, I think the two things make excellent bedfellows.

You are also a well-known puppeteer and puppet maker. Can you tell us a little bit about your philosophy regarding incorporating puppets into live theatre?

I use a lot of puppetry in my work, and also combine magic tricks into the narrative.

The puppets work wonderfully in horror because they are a performance medium that exists entirely in the mind of the audience. A puppet isn’t a living thing. It can’t emote. Or talk. Or move. It doesn’t even really need to look like the thing it represents. The audience is entirely aware that it is an inanimate object being wiggled by a human being. And yet they endow the puppet with life, and motives, and sentience. But all of that only exists in the imagination of the viewer. That is an incredibly powerful tool.

It means that if an audience is engaged in a puppet character, they are operating at a deep level of imagination that few people experience outside of childhood. Therefore, a play using puppets has a tremendous amount of leeway in terms of emotionally manipulating the feelings of an audience. You can make them laugh and cry in close proximity. You can scare them or anger them. You can be assured that they will accept the absurd as commonplace. And all because they’ve already done the heavy lifting in their own minds when they brought life to the puppet character.

Conversely, magic is an art that relies on the skepticism of the audience. You want them to be mistrusting when they are watching a magic bit. You want them to try to guess how things are done. That way, at the climax of a successful magic routine, the audience feels wonder because they have challenged each element of the routine with rational observation and are then forced to come to the conclusion that what they have seen must be impossible. In that regard, magic is the opposite of puppetry. You are forced by the performer to believe magic is real. Whereas, you easily allow yourself to believe a puppet is real.

Using puppetry and magic in close proximity together engages an audience in ways that few other things can, because both their childlike imagination and their adult rationality are operational at the same time.

The Eldritch Theatre has been running an online Sorcery School for tweens and teens during the pandemic. Tell us more!

Every March Break and summer, Eldritch had been running Dungeons and Dragons Camps. When Covid shut everything down last March, some of our parents asked if we would move the sessions online, and we’ve been running them ever since. Our Dungeon Masters, who run the games, are all actors and playwrights. Our kids range from 10 to 16. And it’s been a really successful program.

We are currently accepting enrolment for our fall session, running on weekends from October till December. People can sign up at www.eldritchtheatre.ca/sorcery

What are you working on now?

Eldritch Theatre has two plays coming up in 2022. A double bill of Kafka’s Metamorphosis and Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness will premiere in April. And coming in November is the second part of our Apocalypse Trilogy, Requiem for a Gumshoe, which is a Weird Noir play about the end of the world, a cursed oratorio, and private detective mourning the death of his son.

Both plays will be at the newly refurbished Red Sandcastle Theatre, which has recently come under Eldritch Theatre’s management, and is available for rent for all your theatrical needs… www.redsandcastletheatre.com