Posted April 18, 2023

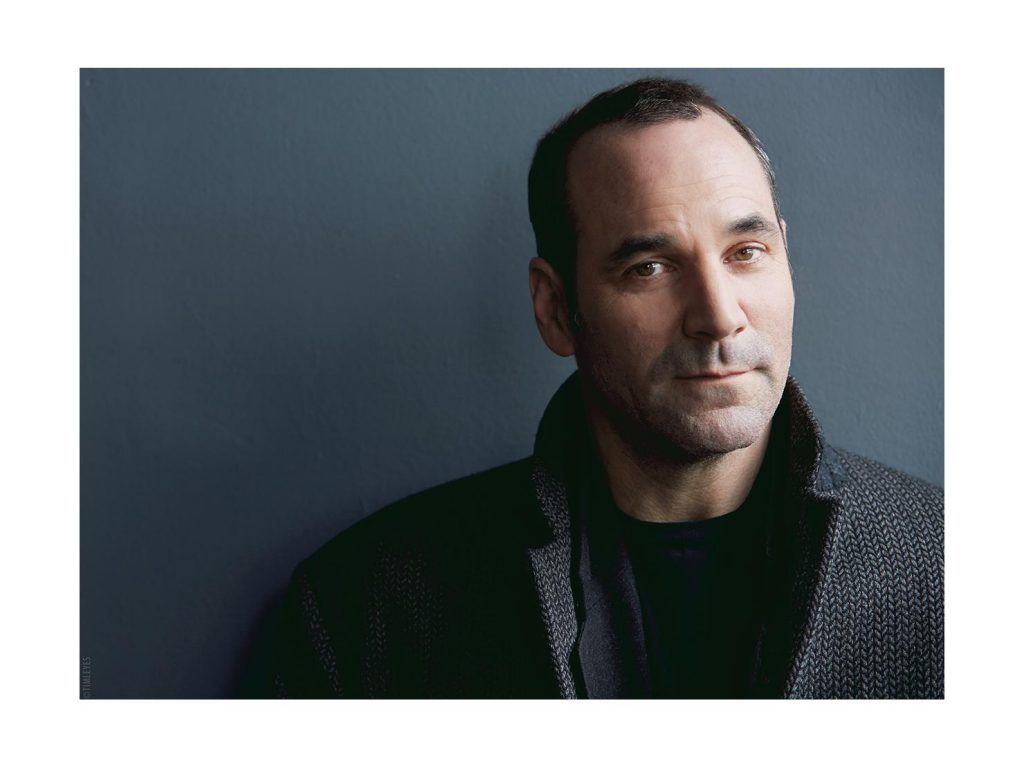

The Interview – Alex Poch-Goldin

Alex Poch-Goldin

Alex Poch-Goldin is an acclaimed playwright and actor whose work has been produced internationally. His plays include Anybody and Nobody, Jim and Shorty, The Bad Luck Bank Robbers, Cringeworthy, Internazionale, The Life of Jude, The Right Road to Pontypool, This Hotel, Yahrzeit, and This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen, adapted from the work of Tadeusz Borowski. Cringeworthy and This Hotel were both nominated for the Dora Mavor Moore Award for Outstanding New Play, and the French version of This Hotel (L’Hotel) won the 2005 CBC/Le Droit prize for best production in Ottawa. His play Yahrzeit won the Toronto Jewish Playwriting Award and will receive its world premiere in Germany prior to touring Europe. Alex was commissioned by CBC Radio to write The Death of Simon Pinchuk, which was recorded and broadcast nationally. He has also developed an orginal television series, Rosedale, in addition to adapting his play Jim and Shorty for broadcast on Bravo Television. Alex lives in Winnipeg.

Many playwrights are known for a particular type of play, but your work ranges widely—from the suspenseful three-hander Cringeworthy, about crime and addiction in Edwardian England, to the epic 21-character Biblical musical, The Life of Jude; from Jim & Shorty, a glimpse into the lives of men living on the streets, to Yahrzeit, a family play that tackles issues of war and peace. Do you think there is a common thread that runs through all of your work?

My friend David Jansen once said that my work was about the underdogs of society. I hadn’t ever thought of that before, but I think it’s partly true. The heroes in my stories always have to overcome great odds that are often shaped by the structures of society.

I think that gives them an “everyperson” quality and makes them very identifiable for the reader.

Your play The Right Road to Pontypool is an affectionate and nostalgic look back at the Jewish summer resort town in Ontario that thrived from the 1920s to the 1970s. It’s a piece of history that hadn’t had wide attention until the play debuted at 4th Line Theatre. Can you tell us why you wanted to tell this particular story— and how you researched it?

The Right Road to Pontypool was a labor of love, and my first commission from 4th Line theatre and Artistic Director Kim Blackwell. My parents grew up in Montreal and used to vacation in the Laurentian mountains outside of the city. It was like a smaller version of the Catskills in New York. And there were areas where Jews were not allowed to go. Many places had signs that said, “No Jews or dogs allowed.” So when Kim asked me, an ex-pat Montrealer, to write about Pontypool, I was curious to say the least. I’d never heard about the resort before, and I was shocked to find out how many Jewish and non-Jewish people in Toronto and the Kawartha region had connections to a place that, for 60 summers, took over a small Protestant town of 300 people, swamping it with 2,500 poor Jewish garment workers and their families who came to vacation in ramshackle cottages by a tiny lake, which eventually blossomed into larger resorts, with entertainment and activities for the community.

So I felt a connection to the story because my parents had imbued a sense of Jewish community in me. And when I met Doris Manetta, whose father had run Manetta’s resort in Pontypool, I began to hear her stories and an overview of that era. Doris had been a dishwasher and ran around doing odd jobs at the resort for many years and had struggled to get out of the small town so she could become a teacher in Toronto. I was so taken by her story that I turned her into one of the main characters in my play. She was delighted, as was I. 4th Line Theatre also does these reminiscences where the community comes together and talks about the events surrounding the play. I got a lot of information from that, as well as from Grant Curtis’s book called Smile and the World Smiles with You in Pontypool, which talked a lot about the establishment of the town itself, and then the influx of the Jewish community. So with all these snippets I had a wealth of material to draw from, and shaped a story that basically covered 100 years from the establishment of a homestead by the first Jew in Pontypool—Moishe Yukel Bernstein—to the demise of the cottage industry, when communities began to become more affluent and choose other holiday destinations.

This Hotel, which won the CBC/Le Droit prize and was nominated for several Dora Mavor Moore Awards, is a surreal journey through the subconscious mind of a man who discovers his wife’s infidelity. It’s hilarious, bizarre, sexy…fantastic in every sense of the word! It definitely bucked the prevailing trend toward realism in English-Canadian theatre. What do you think influenced the style of This Hotel?

I had gotten into the Toronto Fringe Festival, and I didn’t have a play to produce, so I researched some old journals and I found a dream I’d had about infidelity, and it became the inciting incident of the play. This Hotel is a very early play of mine, and Kelly Thornton, who was the dramaturge/director, helped me discover the story, using the hero’s journey as a guide. It was a wonderful structure, and it made great sense to me. I think the story opened up corridors in my mind as I contemplated the possibilities of love, lustful desires, regretful mistakes, the yearning for attention and contentment—all these shaped the journey of Lester, the main character of the piece. I think these reflections on love are things that people can identify with. Wrap it up with a highly theatrical staging and an abundance of humour and the show at Passe Muraille was Toronto’s top-selling play of the year. At the same time, my own personal opinion was that, with the millennium approaching, there was a growing social anxiety, and somehow it really felt like I was able to tap into that and that people responded to those themes in the play. I saw productions of this play in French in Ottawa, and the American premiere in Pittsburgh. It was so amazing to see different interpretations of the play, at the same time.

You began your theatre career in Montreal, you were based in Toronto for many years, and you recently moved to Winnipeg. Tell us a bit about how you have experienced the theatre community in each of these cities.

I love all the places that I’ve lived. In Montreal, where I grew up, I was a student at the Dome Theatre at Dawson College, where I did a three-year program. I became really quite devoted to theatre and acting and wanted to make a serious contribution to the craft. After, I continued my studies at the National Theater Institute at The Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut, where I learned a tremendous amount, especially about people, and that theatre was about people, not about individuals. That’s something that I carry with me very much today. In Toronto, I spent 30 years shaping my career, taking chances, acting, becoming a writer, because, oddly enough, the phone was not ringing with offers from my agent every day. But as a creative person I needed to express myself and so I took more seriously to writing, which I had done since I was a young person. When I left Toronto about 4 years ago it was scary because everything I knew about theatre and theatre people was in that city. I built up a profile through tenacity and hard work and I was also teaching at the Toronto Film School. I had worked in Winnipeg many times over the years and always enjoyed the city and the community, so coming back as a senior artist was exciting, though it has its challenges because you are coming into a place that is not your home. When I got here, the first play I did was Kat Sandler‘s Bang Bang, which we did as a co-production with the Belfry. I won an Evie award for that play and felt embraced by the community, but a few months after the show, the pandemic arrived in Winnipeg with a vengeance. Somehow I managed my way through it, between Zoom projects, writing, and film and TV. I certainly prefer the summers in Winnipeg, but I’m also someone who loves to work and if I’m working, I’m happy. Also, Winnipeg is the home of Scirocco, so it has a special place in my heart.

What are you working on now?

Currently, I am in Edmonton, completing the second half of a co-production of Trouble in Mind with a wonderful company. I am also adding the finishing touches to a play I’ve been working on for several years, called The Trial of William Shakespeare, a very complex and multifaceted play, but basically about putting The Merchant of Venice on trial for antisemitism in 1947 Palestine. The play is about Jewish identity, democracy, the nature of censorship and free speech. The idea was brought to me by my friend Barry Lipson, and I am hopeful it will receive a production in the next year or two. I’ve also just received support for a project about Jewish settlements across the prairies that date back to the 1880s. My researcher, Erin McGregor, and I have collated hundreds of pages of documents and interviews based on government programs to bring European Jews over to Canada to settle the west by establishing farming communities. Many of them did not succeed, but there’s a clear connection to these settlements and the establishment of the Jewish communities of Winnipeg, Edmonton and Calgary. It is a little-known and fascinating history, and I expect that I will create my first documentary style piece of theatre, or at least that’s what things look like from here, at the moment.

Alex, in addition to writing plays, you also act for stage and screen. How does being an actor influence your playwriting? Also: what are some of your all-time favourite acting roles?

I think that acting in different genres made me want to write in different styles. I also learned a lot about dramatic structure working on The League of Nathans years ago with Brian Quirt and Jason Sherman. That experience provided me with my first dramaturgical tools to begin exploring and developing new work. I mean, I lost my shirt on my first play, Anybody and Nobody at Canadian Stage, but it was a baptism by fire. And I’ve always been grateful for festivals like the Fringe, Summerworks, and Rhubarb that helped me get my start, and allowed me to write, direct, and act in a low-risk environment that was highly creative.

I continue to act on film and on stage. Some of my favorite characters that I’ve played are Louis Ironson in Angels in America, which ran for a year at Canadian Stage, Salieri in Amadeus at Talk is Free Theatre, Tony Capello in Bang Bang, and Edmund in Martha Henry’s King Lear at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre. In film and television, I’ve gotten to work with some heroes, like Susan Sarandon in The Calling, and Philip Seymour Hoffman in Owning Mahowny. I feel quite blessed as an artist. I really believe that hard work and tenacity is the only way forward in a creative career. Write grants, do shows for free, trust your instincts and do what you love because that is the currency to pay your way forward. It may not always lead to success, but it allows you to be true to yourself.

-

The Right Road to Pontypool$9.99 – $15.95

The Right Road to Pontypool$9.99 – $15.95 -

The Life of Jude$9.99 – $15.95

The Life of Jude$9.99 – $15.95 -

Jim and Shorty$9.99 – $14.95

Jim and Shorty$9.99 – $14.95 -

Cringeworthy$14.95

Cringeworthy$14.95 -

Yahrzeit$14.95

Yahrzeit$14.95 -

This Hotel$12.95

This Hotel$12.95